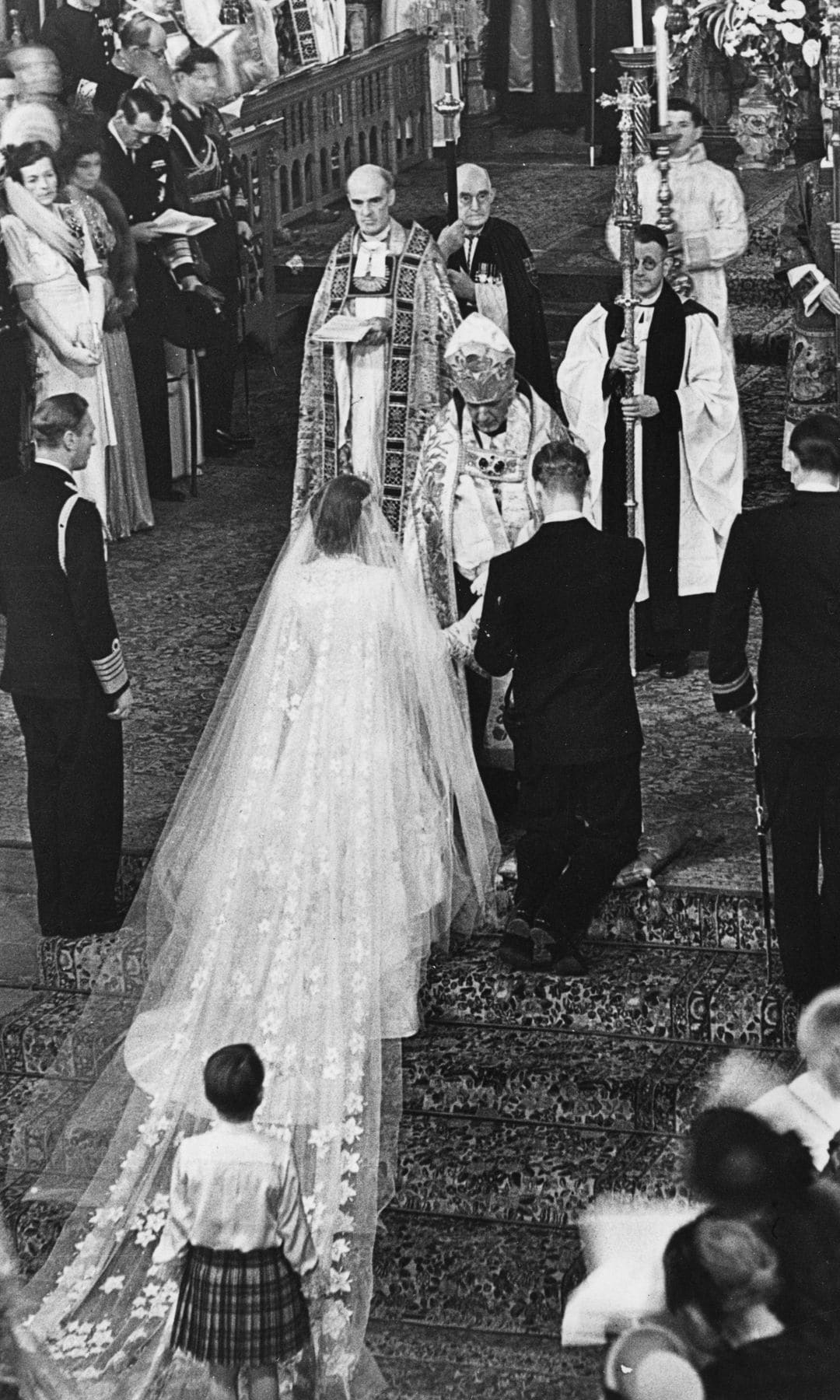

He November 20, 1974 England and half the world woke up expectant: Elizabeth II and Philip MountbattenDuke of Edinburgh, were going to get married in Westminster Abbey before 2,000 guests, but there would be many more people who could follow their wedding. Theirs was going to be the first wedding royal broadcast around the world on BBC radio and the chosen dress by the then Princess would go down in posterity as one of the most iconic designs, marking a before and after in bridal fashion.

A wedding dress on a budget

Before delving into the details of the dress, it is important to put ourselves in context to understand many of the decisions that Elizabeth II made about her dress. The marriage was celebrated only two years after the end of the Second World War. Theirs was going to be the wedding royal of the year, but the budget allocated to pay for the design could not be very large; The British economy, like so many others, was not going through its best moments.

For this reason, Elizabeth II herself collected coupons to be able to pay for the materials that would shape the piece, a gesture with which she aroused the sympathy of the English. Upon finding out that she was saving for the model for her big day, her most loyal followers sent her their own coupons. Finally, seeing the loving response, he ended up returning them when The government decided to increase the budget.

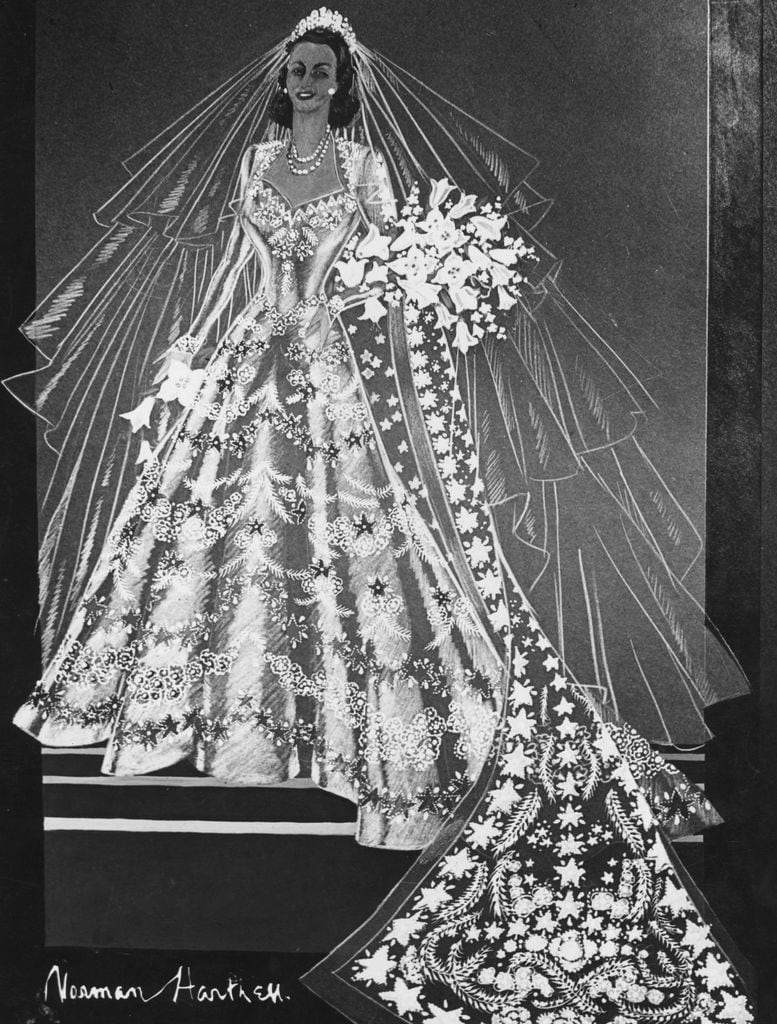

The responsibility of creating the bride’s dress fell to the renowned British couturier Norman Hartnell who, following the fashion dictates of the time, created an ivory design with marked shoulders, tight sleeves, a sweetheart neckline and a wasp waist. A creation that soon became one of the most spectacular pieces of its designer, who came to consider it the pinnacle of his career by declaring it the most beautiful he had created.

To shape the dress, made of silk satin gifted by China, it took 25 seamstresses and 10 embroiderers They worked for weeks on every little detail. And, as is often common in royal bridal looks, symbolic elements are very important.

The embroidery, a hallmark of Hartnell’s creations, was distributed throughout the dress. They included British and Commonwealth floral emblems in gold and silver thread, 10,000 pearls coming from both Great Britain and the United States, inlays of rhinestones and Swarovski crystals. There were also flower and wheat motifs inspired by the work springby Botticelli. And an Irish four-leaf clover, woven into the skirt, which the designer had included as a nod of good luck to the bride.

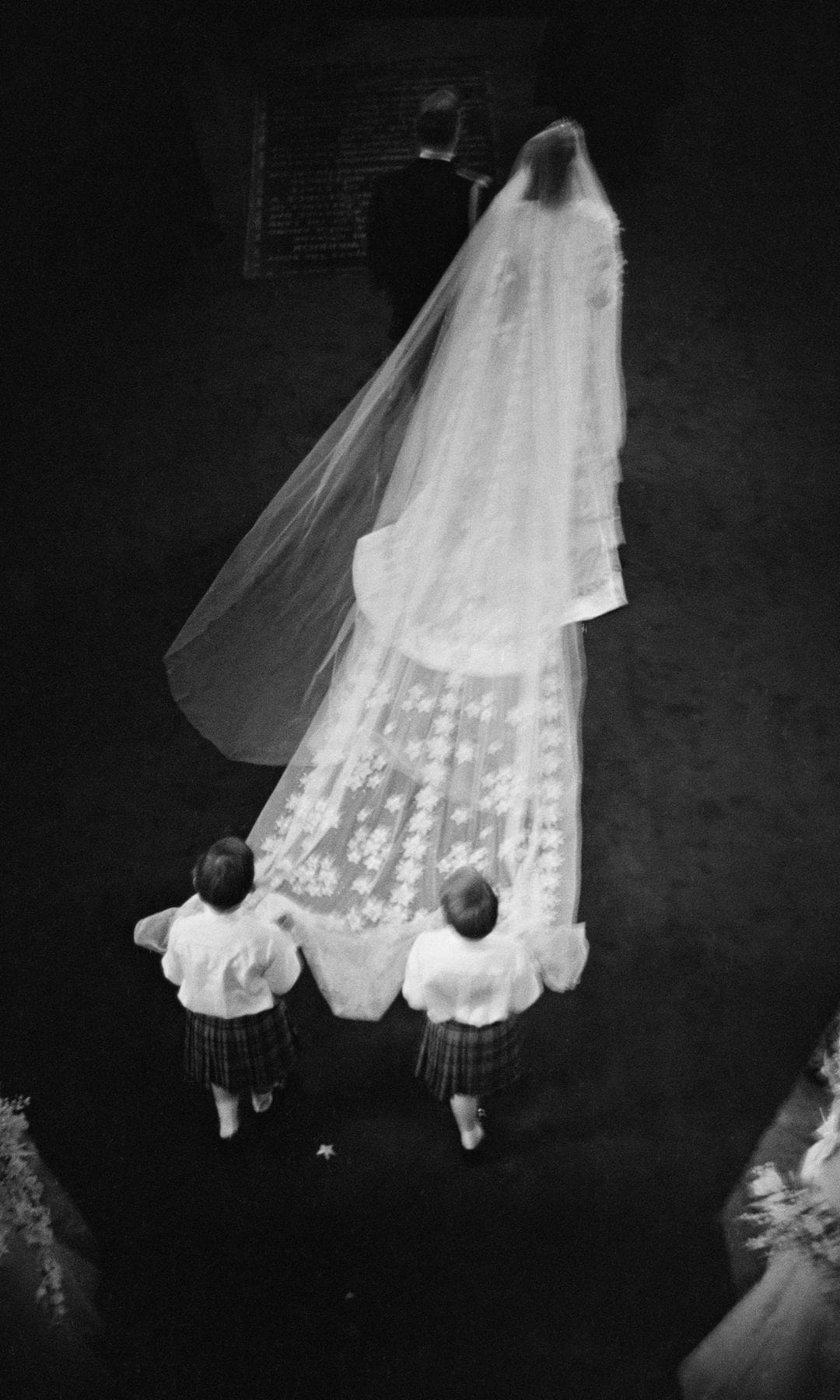

The design was completed with a fan-shaped tail and a wonderful veil made of silk tulle coming from Egypt and embroidered with details similar to those of the dress.

The mishap of the tiara, a missing necklace and a lost bouquet

Being a Royal wedding, there was hardly any room for improvisation, but it was inevitable that some setbacks would appear, one of them related to the tiara. Elizabeth II planned to wear the Fringe tiaraa jewel that had been created in 1919 for Queen Mary with the diamonds that Queen Victoria had given her as a wedding gift. But the piece in question It broke hours before the link. Although her mother proposed replacing it with another, the then Princess refused and the court jeweler on duty had to repair it in an emergency. This express repair is visible in the portraits of the big day, since, if we look closely, it is possible to guess an extra space in the front.

In addition to the tiara, the bride wore some discreet earrings. This jewel was a gift received by the daughter of King George III, Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester. The originals were much larger, but when Queen Mary inherited them, she separated them and gave the top part to Elizabeth II on her twenty-first birthday. He also took a necklace which, again, has an anecdote. This pearl accessory, which was actually two different pieces that she decided to wear together (one from Queen Anne and the other from Queen Caroline), was not with her while she was getting ready, it had been forgotten at St. James and Elizabeth’s private secretary had to go looking for him.

Although it may seem implausible, the saying ‘there are no two without three’ is true in this case. Added to the mishaps with the jewelry was the disappearance of the branch. The renowned florist Martin Longman created a floral composition for Elizabeth II with white orchids and myrtlea plant that has been incorporated into British royal bouquets since Queen Victoria’s wedding in 1840. The myrtle in Elizabeth II’s bouquet was taken from the bush planted by Queen Victoria herself at Osborne House, her residence on the Isle of Wight. But the most striking thing about this waterfall design It’s just that it disappeared in the morning. Luckily, they found it: a footman had placed it in an ice chest so that the flowers would remain in perfect condition.